Last autumn I was the writer-in-residence at the Huntington Library and Botanical Gardens for two months. It was a magical experience—balancing my time between writing and walking and painting cactuses and ficus trees in the gardens, meditating beside the various allegorical statues transplanted from Renaissance Italy, making the occasional offering to Greco-Roman deities scattered throughout the grounds, laughing and smelling the roses in a vast rose garden with names like “Marilyn Monroe,” “Judy Garland,” “Carol Channing.”

I was the first to occupy a new position there as writer, rather than scholar. An anomaly: unlike the others, I was not a fellow in residence who’d had to provide institutional references or pitch an academic project. I had free reign to use my time how I pleased, so I used it to savor as much of the library and gardens I could: What can I do here that I can’t do anywhere else? That’s what I tried to do, see as many books and plants as possible.

One day during the Q&A at an afternoon talk I gave about the work I was doing in the library collections, one of the scholars asked if it was painful to look back at the books containing anatomical drawings of trans and intersex people that the library held in its medical collection. Oh, I know about all those, I’ve seen them and felt that deep discomfort, the queasiness of recognition, but that’s not why I’m here. I haven’t had time to look at them, they don’t really relate to my project. And as a writer one of my tenants is: why suffer? I’m not here to punish myself, I don't think punishing yourself makes for good thinking or good writing. The room let out a collective gasp, some people smiled at one another nervously, like it was a big deal to give that kind of permission to myself.

It was awkward, I guess it had to be, Q&A’s are awkward by design, a pernicious invention. But equally the awkwardness of being visibly trans (the hormones were working), the only visibly trans person there, a new person in a new place not surrounded by friends who got it. People would spot me on the grounds and know who I was right away, come up to tell me about their trans kid, or that they were queer, or just welcome me. Transposed to a Q&A environment I couldn't help but beg the typical question queer and trans people get asked all the time, even by one another: how much does it suck to be you?

It would have felt disingenuous to go too deeply into the depressing experiences I’ve had in archives looking at old files related to Sexology, the days I felt my body trying to force me to fall asleep in a cold hard chair of a climate-controlled reading room just to avoid reading more. And I refuse to tell strangers in that environment about everything I’d gone through to get here, how truly miraculous it was that I made it out of my childhood alive, how the older I get and the more I hear about how other people’s families and how helpful they are emotionally and financially, the more I marvel. On the other hand, being gender non-conforming itself was part of the miracle: the masculinity and femininity shaped by the depressing, angry, blue collar neighborhood I grew up in was a rock & a hard place people never got out from. Lots of the boys my age died from opioids, the girls too, or they got hit hard and held down in all the ways society hates women. I slipped through the cracks through a mysterious power I had—something others noticed and gossiped about and kept their distance from—a power which had names and theories I knew nothing about. My forced feminization saved me at times, and my refusal to be forced saved me at others, I walked a fine line from there to here.

But I’d spent the prior two months at the Huntington essentially organizing my creative life around how much time I could spend in sunbathing with lizards. What can I say, I write my best when I’ve got a good tan. So I gave a few details about a time I’d felt sad in the archives just to perform, like, that I knew what I was talking about! That I got it! I can bravely perform An Archive of Feelings the way some actors can cry on command! I am grateful the world is big enough that some people seek out and write through the tragedy and brutality of the queer past….it meant I could take a break from it from time to time, or avoid it without worrying that no one is talking about this. History is brutal and life spares no one its horrors and hardships, my time had come and would come again to be depressed, but I refused to punish myself unduly in such a pretty place. That feels like a very different process from the kind where great art is made from the transformation (Transubstantiation?) of trauma—a choice that should be made by the creator alone, not forced upon them and not a prerequisite for being an artist. I resent the fact that so much queer and trans art, writing, scholarship—as so much of the art, writing, scholarship of any marginalized group—is not allowed to exist for its own sake, but must exist in relation to oppression. It’s a sneaky form of censorship to force us to keep our wounds open all the damn time.

Of course it’s not like I’m not going to look for queer material in libraries and archives. I’m still interested in whatever little specks of queer or trans existence I can find in any library, and the Huntington is no different. I would just rather find what’s weird and uncatalogued. Who knows what I’ll find and what I can do with it? Who knows how the past has yet to be leveraged by those of us kept out of its narration, collection, dissemination, for so long?

My interest was piqued when I saw there was a stray, single box of materials in the online catalog describes as: “Collection of publisher and bookseller catalogs and prospectuses featuring erotica, most based in New York city, ca. 1930-1950.”

Erotica is a very vague quasi-judgmental catch-all term that comes up time and time again in cataloguing records related to same-sex desire or gender non-conformity. Anything vaguely described is worth looking at—cataloguers are usually not vague, when they are they’ve got something to hide and that’s how they tell you, through omission: LOOK HERE. Looking at collections that are small—one, two, three boxes—is rare in special collections, which tend to accession huge swathes of information at a time, the contents of whole attics and basements and storage units. Small collections are often more miscellaneous, serendipitous, overlooked. Plus you can consult them at a much gentler pace and learn more from less—I would not wish the anxiety or overwhelm I have felt racing against the clock to consult hundreds of boxes of material within fixed opening hours on a research trip of fixed length upon anyone. The story this lurid little box of catalogs and prospectuses revealed to me when I opened it and dug around is a really strange period of American publishing related to LGBTQIA+ people.

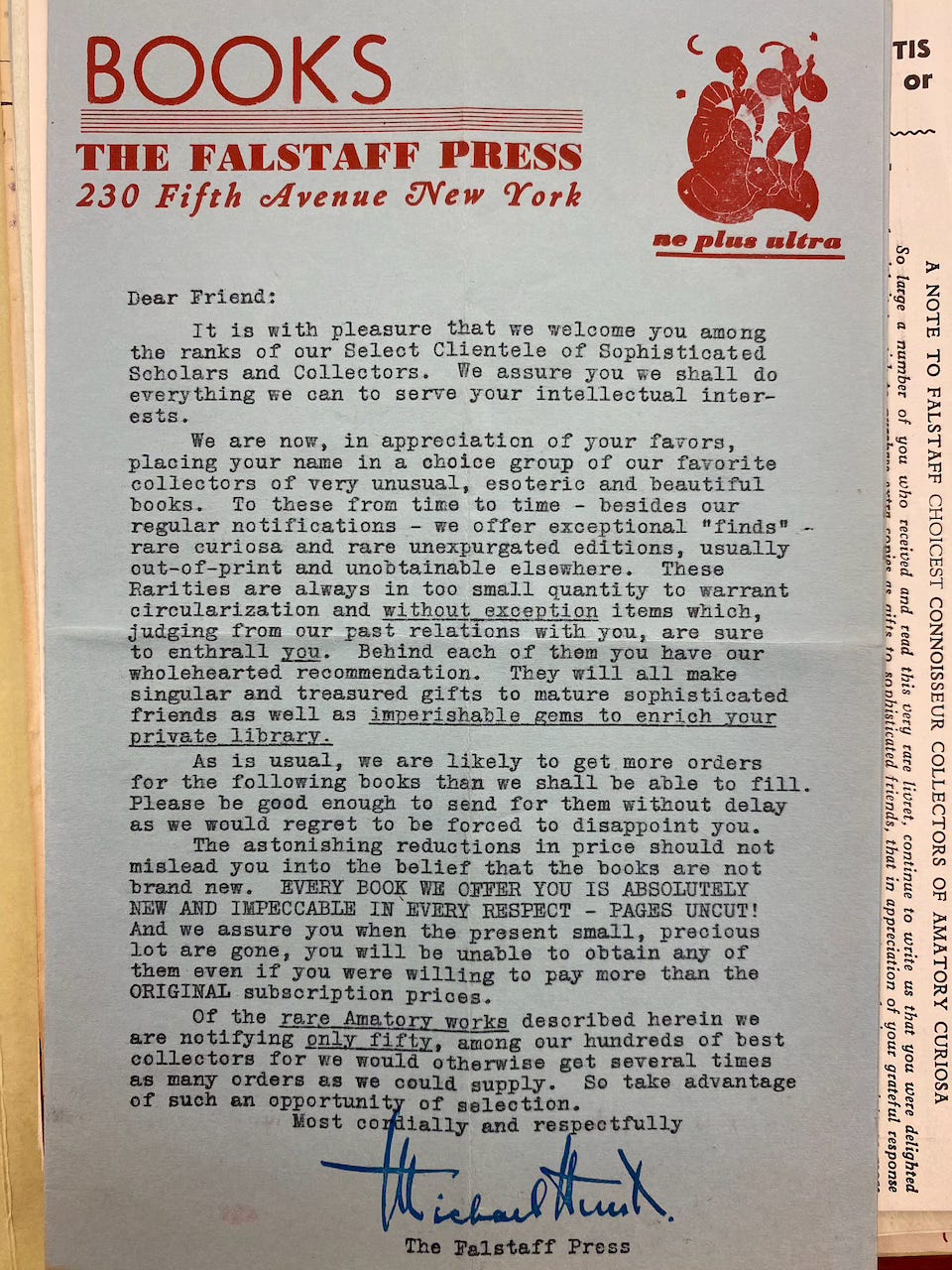

The publishers were mostly based in New York City and included: Black Friars Press, The American Anthropological Society, The Branwell Press, Falstaff Press, and The Panurge Press. The books themselves were advertised for sale by The Argus Book Shop in Chicago, with occasional catalogs issued from Falstaff and Black Friars directly. I found out later, after asking a curator that this midcentury snapshot of book sale and exchange captured by this particular box of items is most likely related to Edwards H. Metcalf’s collecting habits. Metcalf was Henry E. Huntington’s grandson, an avid collector of T. E. Lawrence and packs of playing (and tarot) cards. There was at least one item in the collection that had his name and address on it.

The books offered by these publishers and by Ben Abramson, who ran the Argus Book Shop in Chicago, are the very definition of low camp publishing, in content and form. They situate sexological titles—some of the first US-publications of Magnus Hirschfeld’s writing, for instance—alongside ‘erotic’ literature: Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the diaries of Casanova, and writings by de Sade, Sacher-Masoch, Louÿs, and “the immortal female Boccaccio” Margaret of Angouleme.

It feels like a sick and appropriate burn to place Sexology—a form of knowledge ultimately tied to imperial scientific regimes of knowledge gathering and sorting—as, at best, smutty reading for its lurid and sensational descriptions of sex, since at its worst it has informed a lot of the moral panic surrounding queer and trans people to this day. Many of the books advertised had titillating pseudo-scientific titles: Libido Sexualis by Albert Moll, Passional Psychology by Dr. Jacobus X, Curiosities of Erotic Physiology by John Davenport, Odoratus Sexualis by Dr. Iwan Bloch (“A Scientific and Literary Study of Sexual Scents and Erotic Perfumes”).

To try to circumvent obscenity laws, each book for sale describes itself as meant for adult professionals only (doctors, lawyers, anthropologists). And to materially avoid accusations of being cheap, the prospectuses relentlessly describe the fine quality, design and binding of the publications. They’re Porn described as Science dressed in Tacky Nouveau Riche Clothing pretending to be Rich and Authoritative.

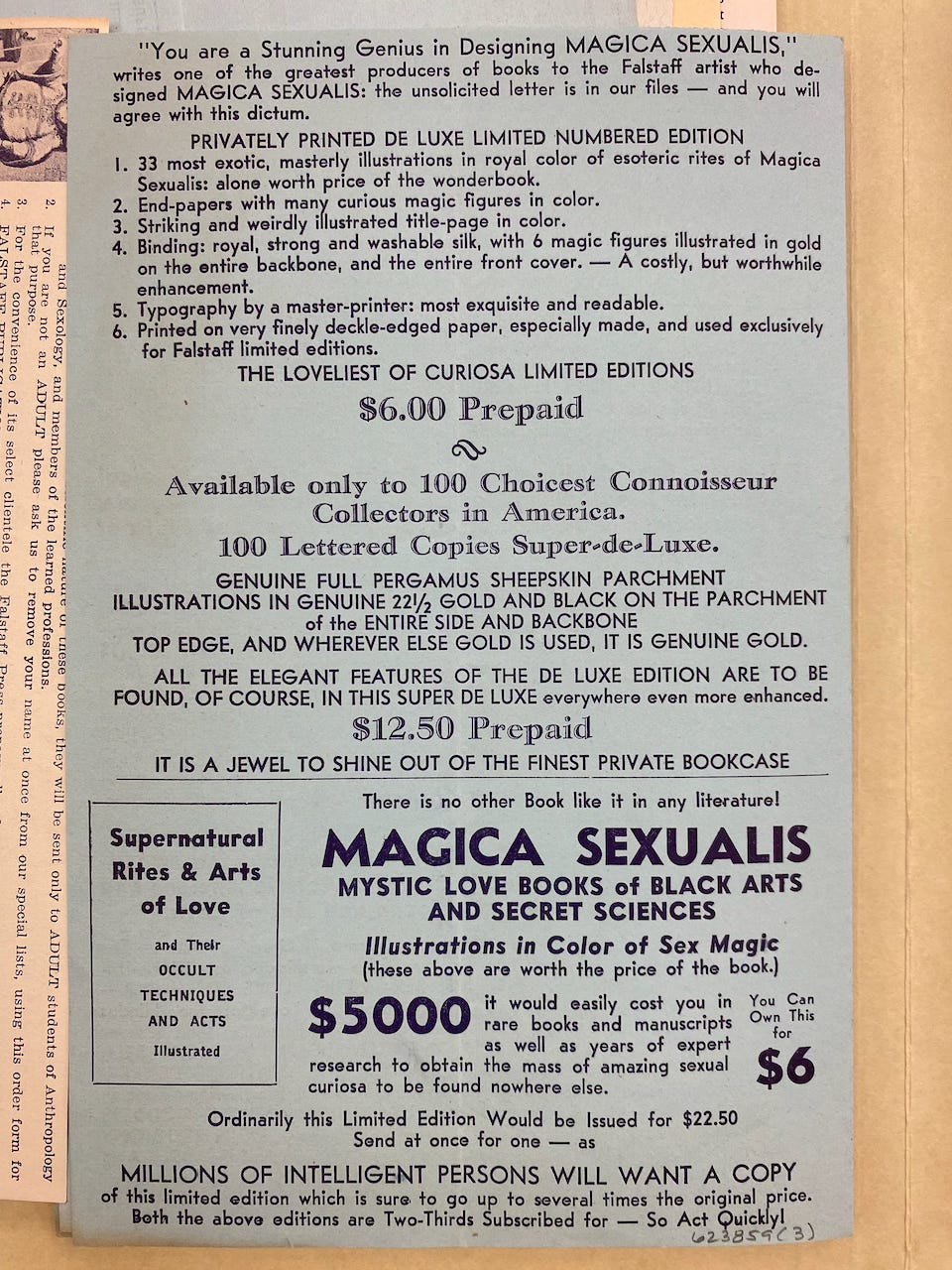

For instance the prospectus for Magica Sexualis: Mystic Love Books of Black Arts and Secret Sciences, published by the Falstaff Press in 1934 describes the book this way:

“You are a Stunning Genius in Designing MAGICA SEXUALIS,” writes one of the greatest producers of books to the Falstaff artist who designed MAGICA SEXUALIS: the unsolicited letter is in out files -- and you will agree with this dictim.”

And “THE LOVELIEST OF CURIOSA LIMITED EDITIONS” “Available only to 100 Choicest Connoisseur Collectors in America”

After elaborate descriptions of the book’s fine quality, the hard sell continues, packaging the book as both a huge bargain that consolidates expensive and hard-to-acquire knowledge in one volume, and a great investment:

“$5000 it would easily cost you in rare books and manuscripts as well as years of expert research to obtain the mass of amazing sexual curiosa to be found nowhere else.”

“MILLIONS OF INTELLIGENT PERSONS WILL WANT A COPY of this limited edition which is sure to go up to several times the original price.”

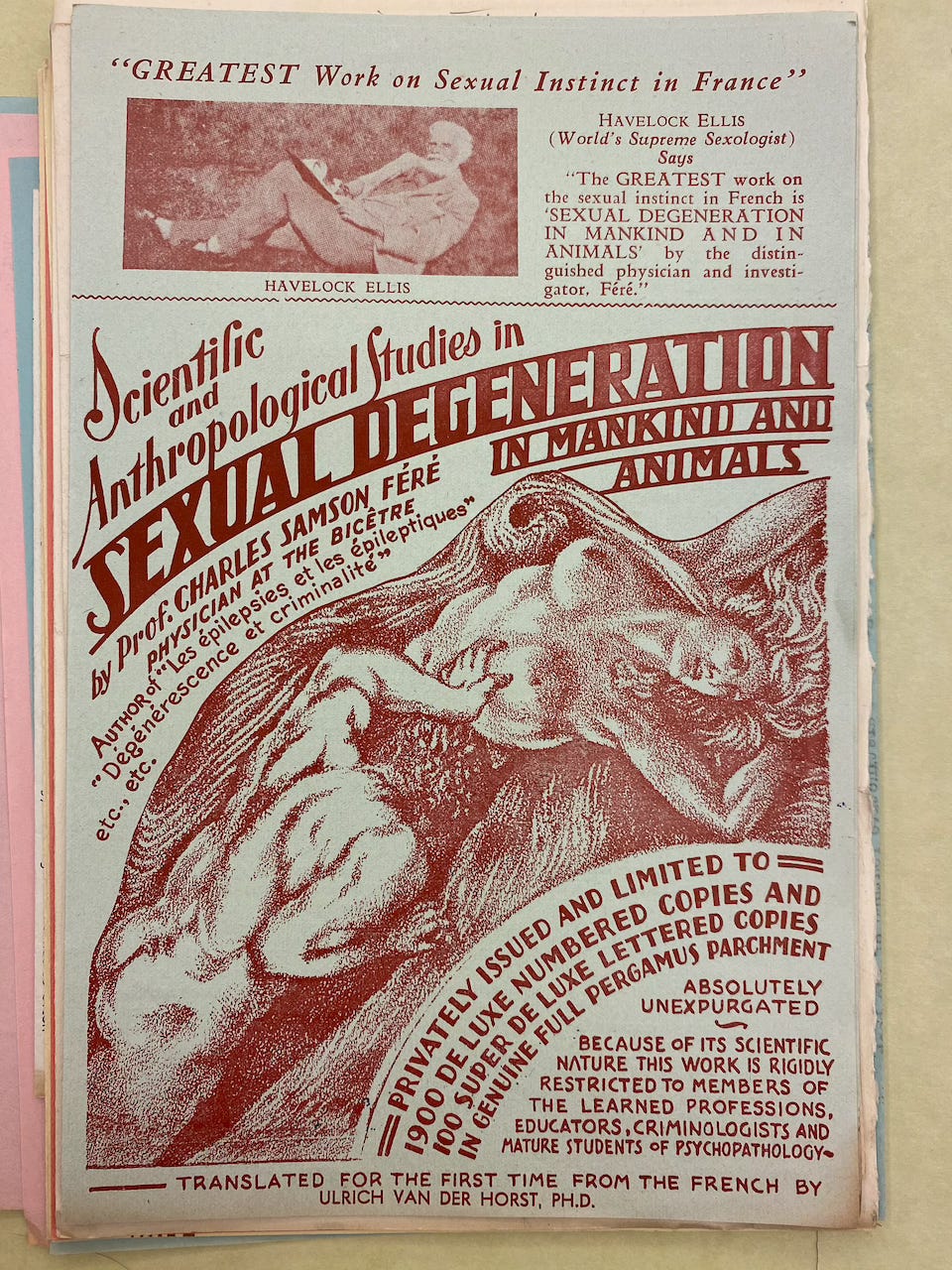

The description of Sexual Degeneration is equally “De-Luxe” and also totally vague. From it’s prospectus:

“The book has been entirely designed by one of the designers of the ‘Fifty Best Designed’ books. It is de luxe in every detail and no expense has been spared to make the format worthy of its extra-ordinary contents. There is a powerful and masterly group frontispiece reproduced in colors. It is a striking work by an Italian artist of fame….SEXUAL DEGENERATION is set in 11 1/2 pt. Scotch double leaded — an extremely clear, pretty and readable type. Especially supervised printing was done on a fine hand-made finished paper produced expressly for this edition, deckle-edged. Royal octavo over 350 pages packed with esoteric information. The entire first folio is in colors! Rich Pelican Binding—Genuine 22 1/2 Karat Gold on Backbone and Side. The book is bound in rich designed black Pelican, by a fine edition binder. Genuine 22 1/2 karat gold was laid by hand on the backbone and side designs. Beneath the gold is a color harmonizing with sprayed top, illustration and title-page. Protective cellophane cover.”

And that’s not even the most deluxe edition of Sexual Degeneration: in “full genuine parchment skin…illustrated by the Italian artist Francis J. Buttera in color in an exotic manner never executive before.” The bibliographic language used to describe the design and components of these works is, by and large, a performance in itself, taking known concepts in the crafts of binding, illustration, typesetting, design, and perverting them with fabricated by vague ideas (“an exotic manner never executed before”).

Some future piece in this substack may get into the weeds about the creation of “curiosa” and “Amatory works” as collectible categories with distinct, inflated bibliographic features—there were so many of these prospectuses and catalogs, many of the books survive, but there has been so little written about the publishers who manufactured and occasionally went to prison for them. By and large, as a marketing push to circumvent obscenity laws, these largely mail-order booksellers sought to install newly printed books into the world of rare, collectible, antiquarian volumes, and it worked. Sneaking these volumes into the market through the trade in secondhand and antiquarian books, and the exclusive, elite club of gentlemen book collectors implied by the trade at this point in its history, was successful to the extent that they remain obscure books, and publishers. Censorship is usually bigger business, great publicity, but these books weren’t banned so you won’t see them on display at your local library.

The network of these catalogues and the volumes they sold are some of the first non-fiction works in the USA to describe queer and trans people as existing in all places and times, albeit one that often pathologized or criminalized us. But they did, however, circulate some of the first volumes which the post-War generation of LGBTQIA+ activists encountered language to describe their situations. And maybe more importantly than giving us scientific language to learn and unlearn, the system of circulating these books was adapted by the first expressly queer bookstores in America to peddle their wares from the 1950s onward: Elysium Fields Books, The Guild Press, The Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookstore. On the other side of the Atlantic ocean, Gay’s the Word started as a mail order bookstore, and in 2018, I started my own queer bookstore that way too.