The sign-in book at the library’s registration desk was as much an initiation into research as it was into gossip, partying, and queer sex. At least that was true when I worked the desk. One of the scholars who visited from out of town had written a book whose title described my situation: Textual Intercourse. The subtitle to his book was: Collaboration, Authorship, and Sexualities in Renaissance Drama, and I was into that. But the subtitle to my version was: Sexual Awakening in My Happy Place.

Some contexts feel impossible to avoid, or are just the most readily available given our habits. Sometimes this feels like the drudgery of capitalism stifling every possibility, and sometimes it feels like fate. It was a little of both here, mundane and magic, I was annoyed it would happen this way and I was ecstatic. My entire life up until that point had been survived through my voracious reading habits. Every need I’d had, every emotion I’d felt, every inclination I’d had to shove deep down into myself, or have smacked the hell out of me, or taken a vow of silence about, or locked myself out of, it had all been surmountable because I could dissociate through reading. So of course it had to be through books that I could begin the process of being slowly decanted back into my physical form. Textual intercourse.

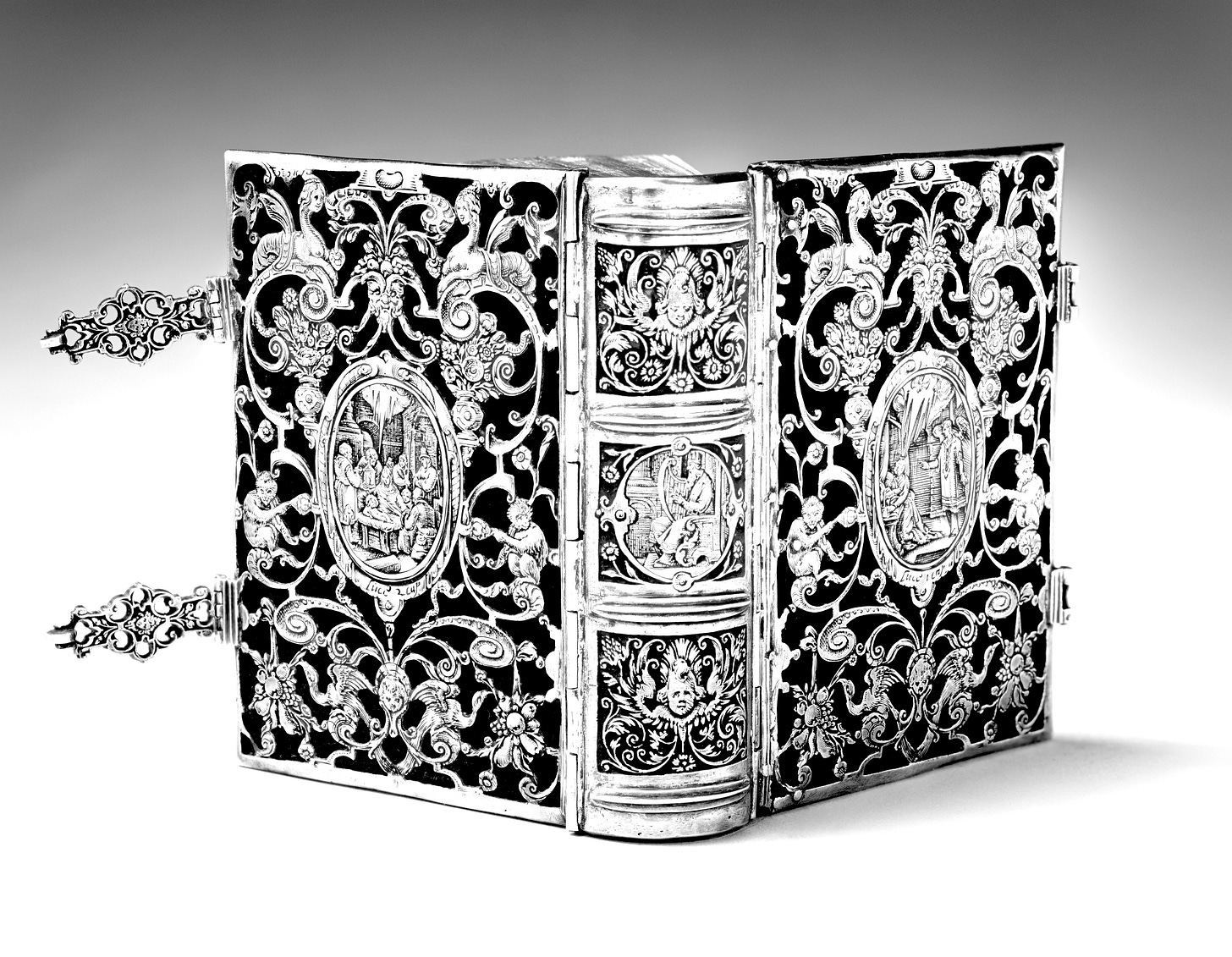

The field of study was called: bibliography, and, the materiality of texts. I had to learn how to sense, feel, make up every aspect of the physical formation of books, from the physical labor of setting heavy lead type and mixing ink and printing to folding pages together and cutting them down and stitching them up and binding them, before I could conceive of doing that to myself, as an embodied person. I had to study fingerprints in the margins, bizarre codes on the endpapers, the corrosive presence of too much urine in homemade ink, forensic analysis of human interactions with 500-year-old books down to the fibres from old clothes recycled to create the paper they were printed on. The book was a body to me, and also kind of meeting place in which many bodies had sweat together. I had to learn to sense the presence of all these sweaty bodies labouring to get these words into my hands before I could become embodied to myself.

The sixth floor of the library, where I worked, was a lot like my body then: restricted, but with a taste for the finer things. It wasn’t like the rest of the library, with open stacks for browsing and books that could be taken outside the building to line your own shelves in your own room. People came to us from far and wide. It was a special collections library and archive featuring highlights and treasures from across documented history: long medieval scrolls detailing the births, marriages, and deaths of rich people, the first folio of Shakespeare’s works, too many rare bibles and one of the largest comic book collections anywhere, letters written by Walt Whitman, letters written to Walt Whitman by America’s First Faghag, Anne Gilchrist.

There was a stunning breadth of material on the history of alchemy and the dispersal of its secret knowledge into the sciences as we knew them today, there were endless pamphlets containing plays, more with fire and brimstone sermons, and there were new collections were being added all the time, always some shiny new-old dead thing to behold. To access these materials you needed a reason, however tenuous, and the glass reading room had a special lock that whomever worked at the desk would operate to let people in and out. My reason was the best reason: I worked there and the librarians and curators were so kind to me, so enthusiastic about my enthusiasm, that they let me linger with any book or slip of paper I wanted.

You’d ring the doorbell and we’d lock eyes, I’d let you in and you’d have to sign into the guest book: Name, Address, Phone Number, Institutional Affiliation, if any. Then you’d take little slips to fill out, calling up whatever you were researching, and that was the source of my real education. Picking classes on subjects I was attracted to didn’t satisfy my appetite even then: I needed to be somewhere surrounded by people who knew things I didn’t and let chance take its course. Through the serendipity of my shift schedule and their research timeline, we’d come together and these visitors would tell me about the most amazing things, things I’d had no idea could survive, things I never thought I’d hold in my hands on the way to putting them into theirs, things I wouldn’t have even known how to look for. Most of the people doing this work were gay men and lesbians.

I needed to work with these books as objects before I could objectify myself (and let myself be objectified in all the ways I wanted to), in order to reach, finally, a subjectivity that suited my needs. The parallel is clear between what I was undergoing and what I cared about in the history of material texts, as described by Judith Sill and Michael Worton in the introduction to their collection Textuality & Sexuality: Reading Theories and Practices:

“The major thrust of our argument is thus that we reject essentialism, be it of text, art or woman/man. Texts, like individual women and men, are socially constructed, whatever may be their features of specific individuality. Textuality implies the relative and mobile form of a structuration (i.e. a structure which is not fixed by constantly changing) from which significations can be produced by a subject -- which is itself partly constructed by encounters which can themselves be understood as textual. In other words, our use of the term textuality insists on the following points:

(i) the accessibility of material to significations;

(ii) the inessential quality of signification (i.e. meanings are not fixed for all time even though some meanings persist over considerable time periods);

(iii) the potential fluidity of textual structures (including social networks) over time and place;

(iv) the permeation of (textual) relations by power;

(v) the intertextual quality of textuality.

At the time I didn’t dare take a class in queer theory but I learned everything I could about these people I longed to be close to: from the books they read, the ideas that kept them up at night, to the coffee shops they went to, what they drank in them, the bars they’d go to avoid students like me, the songs they’d sing to their partners at karaoke. I was learning homosexuality—as Foucault might say—as a way of life, as a way of friendship, before I was learning about it as a series of sex acts. Easing myself in. I loitered, I went to every event held at the library. The lovely event coordinator knew me and she told me one day that she made sure the catering to each event was varied because she wanted to make sure I was eating balanced diet—I was always so broke—but the library was feeding me in more ways than one.

Everyone who visited had a different research project and it was all such a turn on: the companionship of Ruth and Naomi, crossdressing in Shakespeare, Walt Whitman’s attempts at having his author picture in Leaves of Grass edited to enlarge the bulge in his crotch, the censorship of Petrarch’s erotic poetry, the sensuous illustrations within botanical books, the transcription of medieval prayer books. There was a regular visitor who believed conspiracy theories about the 1946 discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls and was using our collection to prove that they were 20th century forgeries. No sexual tension there, just genuine appreciation for his devotion to the field—this was 2006 and some of the conspiracy theories circulating at that time were still fun, were merely about uncovering hoaxes related to intellectual elitism and gatekeeping, a hierarchy I was eager to see destroyed. A hierarchy I was already destroying with my very self as a total weirdo with a blue collar background who felt like my ability to handle all of these priceless goods was, itself, a kind of trick. The thrill of being where I shouldn’t, of tracing my greedy little fingers down every leather-backed spine.

Going to college and working in the library in particular felt like the beginning of a major scam I have been running ever since: I could talk my way into opulent places with multi-million-dollar collections of priceless items I cared about and luxuriate among them. I don’t need to own them, I merely want the sweat of my hands to mingle with the ribbed sheets of 16th-century paper made from spun flax and covered in some unknown reader’s sassy observations in the margins. I didn’t need to experience the thrill of possession; they possessed me. One room had been turned into a 19th-century, two-story wood-panelled study with wraparound, bespoke glass-cabinet book shelves containing an exhaustive collection of books on witchcraft, heresy, the workings of the Inquisition, compiled by Henry Charles Lea (1825-1909). It had been lifted wholesale from Lea’s mansion in Philadelphia and rebuilt on the sixth floor. I could take classes there. I could sit there in silence on my lunch break. I could wear a $5 thrifted tweed suit jacket and sit at Lea’s desk under his busts of dead Romans and say in all honesty: This Is My Life Right Now.

The idea that I’d made some decisions that had brought me here to eat my Spicy Chicken Crunchwrap Supreme surrounded by total grandeur felt like a major feat of survival that I promised I would never take for granted, and it was certainly the beginning of camping it up for me. And as an utterly debased form myself, I was putting the Low in Low Camp, the kind Christopher Isherwood laughs at in The World in the Evening, an incredible book about latent homosexuality, bored rich people, and being haunted by your dead wife’s literary correspondence. Or I was bringing Low Camp to High Camp, So Many Expensive Books In Expensive Places. “The relation of Camp taste to the past is extremely sentimental,” Susan Sontag sez in “Notes on Camp.” I’d been reading Sontag at the time and felt in her lists some resonance with what I was indulging in:

55. Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation - not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy.[…]

56. Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of “character.” . . . Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as “a camp,” they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.

57. Camp taste nourishes itself on the love that has gone into certain objects and personal styles.

All of the feelings I had tried not to feel were first felt across the difference rooms, vaults, balconies, storage facilities of the sixth floor of the library. But in using the space of the past to indulge myself in my growing desires to fuck around and find out among Philly’s prolific scene of dykes and fags, I was, as has always been my way, sharpening my emotional and physical awareness in preparation to majorly unleash myself. As Arlette Farge writes in The Allure of Archives: “You realize that it is an illusion to imagine one could ever reconstruct the past.” My camp sensibility was to drag old debris around myself to shape my present and future. And: “The archive is an excess of meaning, where the reader experiences beauty, amazement, and a certain affective tremor.” I was affectively tremoring all right. But I was also creating a space of beauty and pleasure as a counterformation to the deeply homophobic and transphobic world I’d grown up in. I was worldbuilding. To steal from Timothy Leary: I was very carefully constructing my set and setting so that the sexual psychadelia I was about to run headlong into would be as mindblowing as possible.

After a few years of this kind of high holy habit keeping in the library, lightning struck. One day, a woman came in and signed her name into the book while I was there. The smell of her perfume flustered me. (I wouldn’t know the scent as patchouli until much later, but soon I’d have to avoid the smell of it for a year and a day just to get the six months of her off my mind.) After she filled out her information she looked into my eyes without blinking and said: This is pointless. They never even use this information. But you should make it worthwhile, why not take down my number and call me sometime?

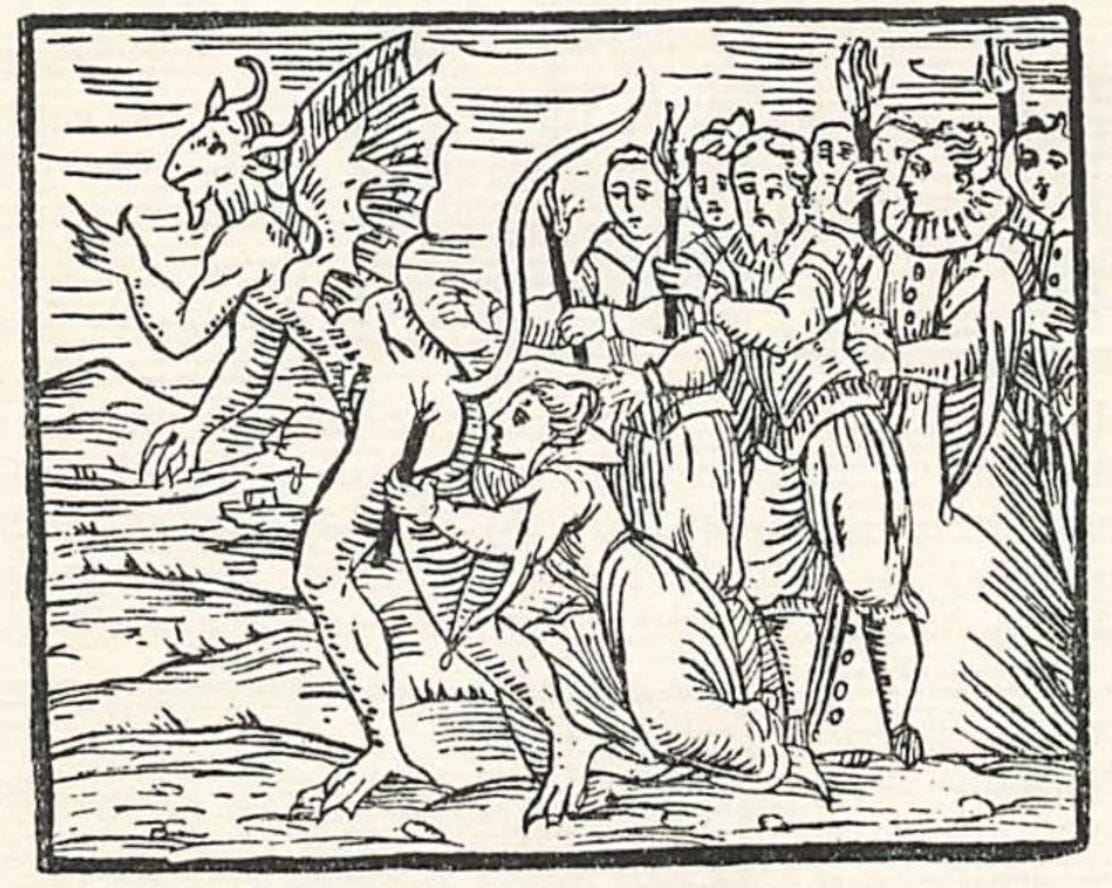

Descriptions of the initiation rites of witches dating back to the frenzied, violent mass trials of the 16th century begin with signing the Devil’s book. Part guestbook, part grimoire, even among illiterate populations it was the way to attain infernal, supernatural power. And I was illiterate in my own way: not out, not using labels, not speaking in familiar tongues yet or at least not fluent in the language of closet, Stonewall, everything that came after. You’d sign the Devil’s Book and give him a rim job. That was unholy fucking: sinful, heretical, mysterious, ecstatic, and that signature and rimming was thought to give the doer incredible powers.

This felt like a reversal of fortunes, the devil signing her name in my book and binding me to months of relentless obsession, initiation into the kindest and the cruellest aspects of queer dating culture, wild promiscuity, exactly the kind of heartbreak I needed to crack myself open to the world, and of course, a masterclass in lesbian processing.

Stay tuned for

THE NEXT INSTALLMENT: